My mother always said that life offered a feast or a famine and never a steady balanced three meals a day which might keep our blood sugar and nerves steady. No, it was a juddering, shuddering rollercoaster ride, swinging from gluttony to a wafer and water diet, and I should always be ready for either.

This year so far has certainly been of a generous rather than miserly disposition. I’ve been immensely fortunate with productions and commissions in 2019/20 and pause now, just post-midsummer, with my head spinning and my belly fit to burst. This, I promise you, is not gloating – the famine months will be upon me again soon enough, and I know from past experience what bolsters me through those lean times is the memory of small celebrations when things were bowling along famously, thank you very much. Success and steady employment is scarce enough in this business, so should be celebrated when it dallies in the neighbourhood. But as my friend Chris reminds me, it isn’t entirely luck when things go well, but a reaping of the benefits of work we seeded long ago. And so like the cricket in the fable, I am singing in the sunshine, but also trying to be the ant and prepare for the future.

Aesop’s Fables, Unicorn theatre.

Fables have been very much a companion the past few months as my first small commission for Unicorn Theatre goes into production. “Working in theatre with young audiences is a total privilege and helps make you a better artist” Aesop’s Fables directors Justin Audibert and Rachel Bagshaw said in a recent interview and I totally agree.

My writing commissions when I was starting out were for young audiences, and the first thing I think about when approaching a new script is considering who will be experiencing the event I hope to create. It directs the story, tone, aesthetic and theatre style. After huge state of the nation plays about death, difference, diversity and disability, it was hugely enjoyable to return to thinking about a young audience, and how to select and make current one of Aesop’s Fables for The Unicorn Theatre’s summer production.

Jessica Hayles and Guy Rhys in ‘Dog and Wolf’ by Kaite O’Reilly, Unicorn Theatre. Photo: Craig Sugden

I chose ‘Dog and Wolf’, a little known fable from Aesop’s trove, as I needed to find something that could have resonance for contemporary times and one that could be political (as in the personal is political) rather than archaic or moralistic. Aesop is often associated with ‘the moral of the story is…’ but there’s no moral here, it’s a teaching, which is just as well, as I abhor moralising. I think it’s better to engage through raising curiosity or empathy rather than through the flawed binary of right or wrong. This pithy fable explores quite complex relationships and issues – of ‘ownership’, hierarchy, freedom, and work/life ethics and fitted my politics of preferring to be hungry and free than well fed but not owning yourself.

I hasten to say, my looping, punning, tongue-twistery treatment of the fable may indeed verge on the post-dramatic, but it’s not as worthy as my hand-wringing description, above, suggests. Co-directed by both Justin and Rachel, it appears in the repertoire for both age groups, 4-8 year old and 8-11 years, and runs until August.

I’ve been thinking a lot about perseverance and longevity in career of late. It’s largely due to mentoring two brilliant but vastly different creatives, Gemma Prangle and Lisette Auton. The conversations we’ve had are as instructive for me as them. We’ve been thinking about trying new processes and form, discovering voice and tone while trying to beat that old bug bear, imposter syndrome. Both women are phenomenally talented and forging ahead with new practice and projects. It’s an immense privilege to be going part of the journey with them, reminding them that no, there is no one way to do anything, and part of their task is finding what works for them, and to hell with all the advice and theories about how to… I’m sure I’m not the only one who wasted an inordinately long time worrying that my process wasn’t like what the manuals or the best-selling authors or the Oscar winning screenwriters said was needed to succeed and get ahead.

‘Just do it’, I said during an impromptu lecture with members from Youth Theatres of Ireland who attended a performance of my play Cosy at Cork Midsummer Festival. It’s not the first time I’ve been photographed outside a theatre with a large percentage of the audience, nor will it be the last time I’m suddenly press-ganged into an impromptu Q&A. I love it. It’s refreshing and invigorating to speak with our emerging practitioners and the future generation of theatre makers. These young creatives were spectacular, full of insight and curiosity, with a strong social and political conscience. Irish theatre is going to be just fine if these are the makers of the future.

Members from the Youth Theatres of Ireland with me outside the Firkin Crane, Cork, prior to a performance of ‘Cosy’ by Gaitkrash.

Cosy at Cork Midsummer Festival was delicious, a wonderful experience of working with six female performers, playing age 16 to 76, at the top of their game. The following short video interviews can give a taste of the company, Gaitkrash, and the lively dynamic whilst dealing with the subject of death from performers Regina Crowley, Mairin Prendergast and Pauline O’Driscoll https://vimeo.com/341828036

http://https://vimeo.com/341828036

The director, Phillip Zarrilli, has his own playful riposte on the subject. https://vimeo.com/345047366

http://https://vimeo.com/345047366

July continues being female-collaborator led, with research and development on a new commission from Wales Millennium Centre, building on my 2017/18 Major Creative Wales Award from Arts Council Wales which had me exploring ‘The Performative Power of Words with Music.’

Sophie Stone and Rebecca Applin in rehearsal in Wales Millennium Centre

Working with long term collaborators composer Rebecca Applin and performer Sophie Stone is an absolute dream, and I will be opening up more about this innovative project later in the Summer.

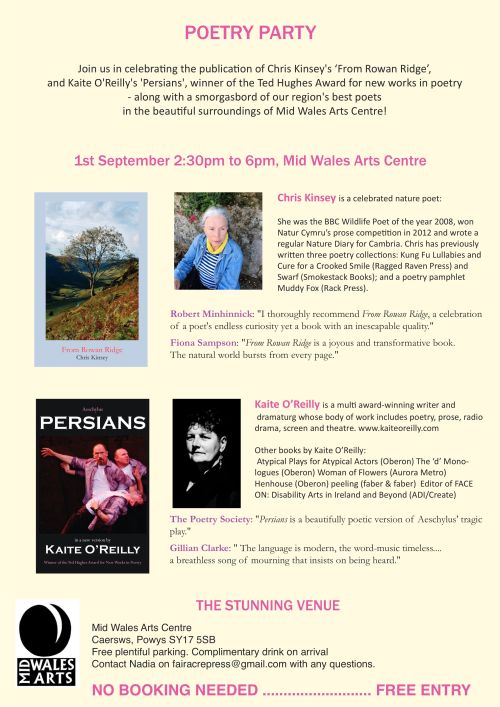

Meanwhile also in July is the book release of ‘Persians’, winner of theTed Hughes Award for new works in poetry, published by Fair Acre Press.

We will be having a Poetry Party on 1st September at Mid Wales Arts Centre – celebrating ‘Persians’ and the publication of brilliant poet Chris Kinsey’s ‘From Rowan Ridge’, also published by Fair Acre Press. The event is free, and will feature readings from our new books, plus a host of invited poets from across Wales.

Persians’ will be published by Fair Acre Press on 29th July 2019, but advance copies can be ordered from the publisher here. It will also be available via Amazon, online, and all good bookshops from the publication date.

I also have other launch events and workshops happening in early September, with a few places left on my masterclass in adaptations at Small World Theatre, details here.

Launch and workshop:

I will be launching Persians in Cardigan at Small World Theatre on 7th September, following a workshop on adapting ancient texts:

Singing the old bones – new stories from ancient texts.

Small World Theatre | Theatr Byd Bychan

Cardigan | Aberteifi, SA43 IJY.Booking:

Playing the Maids: Austerity, Inequality and the Tyranny of Glamour: Wales Arts Review

In the week that the excellent Wales Arts Review relaunches with an improved website and more in-depth analysis, I’m delighted to see my last production, ‘playing The Maids’, an intercultural, international collaboration with Theatre P’yut (Korea). Gaitkrash (Ireland) and The Llanarth Group (Wales) is prominently featured. At a time when theatre reviewers of national newspapers are no longer supported to go outside the capital to see work, initiatives like Wales Arts Review become even more the life blood of cultural engagement and analysis. What is particularly gratifying is the joy with which the talented writers of Wales Arts Review undertake this serious task. It is a pleasure and relief to have the journal back and I highly recommend it, whether you are based in Wales or not. You can find cultural commentary, arts coverage, reviews, commissioned new fiction and a whole lot more at http://www.walesartsreview.org Subscribe. Remarkably, it’s free, and feels like a gift dropping into your email in-box.

What follows is the insightful and informed essay by Phil Morris. The full copy, with images, can be viewed at: http://www.walesartsreview.org/playing-the-maids/

PLAYING ‘THE MAIDS’: AUSTERITY, INEQUALITY AND THE TYRANNY OF GLAMOUR by Phil Morris for Wales Arts Review

When theatre occasionally wriggles free from the straight-jacket of linear narrative there is, perhaps, no more effective art-form for interrogating the contingencies and potentialities that surround a single moment of space-time. In such a moment, charged with the twin forces of past and future, it is possible to feel the weight of history upon the present while, simultaneously, being able to intuit the profound consequences of events that are still in flux. The considerable achievement of playing ‘the maids’ – a dazzling intercultural collaboration from the Llanarth Group (Wales), Gaitkrash (Ireland) and Theatre P’yut (Korea) – is that our contemporary moment of global economic crisis is explored, with great clarity, purpose and theatrical power, from the multi-perspectival viewpoint of nine creative collaborators from four countries, working in four different languages and from a variety of theatrical and musical traditions. The intellectual rigour of the piece is impressive, in particular its meta-theatrical treatment of Jean Genet’s modernist masterpiece The Maids, but crucially at the heart of the piece is the stark reality that the product of economic and gender inequality is only human suffering, rage and despair.

The choice of The Maids as source material for a piece about inequality seemed particularly apposite for the creative team, as cellist Adrian Curtin – who provided the musical accompaniment and vocalised stage directions in performance – explains: ‘In Genet’s play, servitude is toxic and corrosive; it ensnares all involved and is perpetually dynamic.’ The mutual entanglement of mistress and servant in a dynamic of power infuses Genet’s work with a disturbing atmosphere of menace, eroticism and exploitation, which remain relevant to modern audiences. Curtin adds, ‘Where is power located? What guises does it take? What are its effects? Genet’s text provided an excellent framework with which to explore these questions’. However, the globalisation of the world economy in the past thirty years, and in particular the ‘rise’ of the Asian economies; coupled with decades of feminist and post-feminist thought, have complicated the question of economic and gender inequality beyond the rigidly class-based politics of Genet’s play. Director Phillip Zarrilli says: ‘[W]hen we initiated our collaborative process, we agreed to use Genet’s play as a ‘foil’ – a beginning point for responding in new ways to the powerful issues that underlie the play’. The result is a performance piece – it resists simple definition as a play – that responds to the complexities and nuances of modern globalised capitalism and the legacies of imperialism.

This collective decision to use The Maids as an inspirational source, rather than as a primary text that the production might serve, was not only important in terms of liberating the nine creative collaborators to explore beyond Genet’s analysis of power, it also meant that a fully intercultural collaboration between them was made possible. The aspirations of multiculturalism are laudable and desirable with regard to militating racial discrimination and encouraging religious tolerance, but in practice it too often works to eradicate genuine cultural differences in pursuit of its aims of social integration or assimilation. Interculturalism is concerned with dialogue and exchange, it recognises and insists on difference but does not recognise the dominance of one culture over another. In Cultivating Humanity Martha Nussbaum observes that interculturalism recognises ‘common human needs across cultures and of dissonance and critical dialogue within cultures’. With the intention of creating a performance piece that would question, criticise and satirise the power interests of global capital, neo-imperialism and the super-rich oligarchs of East-Asian economies, the imperative of finding some ground on which an intercultural dramaturgical dialogue could take place was clear to all involved in playing ‘the maids’. Genet’s play was therefore situated as a meeting point at which each creative collaborator could engage as theatre artists, all incorporating their own cultural-specific responses to the source play within the process of play-making.

Writing in Exeunt, Irish-born Wales-based playwright, Kaite O’Reilly, describes how intercultural dramaturgy makes particular demands of its collaborative creative partners, in that the customary defined roles of ‘director’, ‘writer’ and ‘performer’ become somewhat opaque, as each member of the company is required to introduce material of some kind toward the development of the piece.

‘In other productions, roles have been clear and the lines agreed and drawn … In this fascinating collaboration roles have deliberately been as porous and overlapping as the creative process. All nine company members have taken equal part in proposing material, leading exploratory material-generating workshops responding to the source from our particular cultural and artistic perspectives.’

Allowing typically prescribed creative roles to become ‘porous and overlapping’ can liberate and empower individual performers to coalesce as a richly-textured ensemble, equally, it can also threaten unnecessary confusion and chaos in the rehearsal room. It is therefore essential that working relationships of deep mutual trust be established when creating work in the open and inclusive manner described above. Happily, playing ‘the maids’ benefitted from what O’Reilly describes as ‘the firm foundation created by previous collaborations between the various artists involved.’ Crucially, Zarrilli has worked for a number of years with all five actors involved in the project, who have each received training in the director’s psychophysical training.

The psychophysical process has been developed by Zarrilli from the mid-seventies, with the purpose of preparing and awakening the ‘bodymind’ of the actor. It incorporates physical, mental and spiritual exercises drawn from Chinese taiquiquan, yoga, and the Indian martial art Kalaripayattu. It must be stressed that Zarrilli’s techniques are not designed to produce a specific movement-centred style of performance, nor does it reject the ideas of Western theorists including Stanislavski; rather it would be more accurate to characterise psychophysical training as a pre-performative approach that enables actors to become more aware of their energy, and, as a result, more capable of deploying it effectively in performance. It is also a means of sharpening the actor’s mental focus. Jeungsook Yoo, who plays one of the maids, Claire, values the approach as a means of delving ‘into wider possibilities of their bodymind and acting beyond the conventional mode of actor training and mainstream acting style where words, narrative and psychological character approach occupy the central position.’

The fruits of Zarrilli’s methodology are clear to see (and hear) in playing ‘the maids’ – it has been a long time since this critic has observed a cast that is so evidently and intensely listening to each other. They make the act of listening palpable, and imbue the performance space with a concentrated energy that is utterly riveting, especially during moments of silence and stillness. Given the nature of intercultural exchange, it is of critical importance that each onstage performer fully commits to each act of speech and of listening, so that surprising and provocative relationships between different cultural traditions might emerge and engage meaningfully with each other. A good example of such a relationship developing in performance comes as Jeungsook Yoo performs a dance called Salpuri. The dance derives from Korean Shamanistic tradition and it is purportedly meant to release Han, which roughly translates to English as an expression of deep collective or personal suffering. The dance is accompanied by Irish actor Regina Crowley, who sings a song of lament, in Gaelic, which references that painful time in Irish history when its indigenous language and culture was banned by the occupying British Empire. Of course, Salpuri and Irish folk songs are highly individual products of separate historical processes that are unique to Korean and Irish culture, and are therefore not necessarily expressions of the same thing. Yet when they are juxtaposed next to each other in performance certain resonances are made available to an audience, as respective national memories of imperial oppression, famine and war are communicated to offer tantalising new meanings.

Complex cultural inter-relationships find witty expression during what is perhaps the most entertaining passage of playing ‘the maids’, when Jing Hong Okorn-Kuo, playing Madame, sings a pop song in mandarin. The Singaporean actor performs this high-camp number with gestures that quote from the performative traditions of Beijing Opera and Chinese soap operas. At the same time, the two Korean actors dance Gangnam style while their Irish counterparts do a jig. In counterpoint to the Chinese music Adrian Curtin starts to riff on the theme tune of popular sitcom Father Ted on the cello. Each of the performers appears to delight in sending-up the clichés and stereotypes of their own cultures. The effect is to balance the more challenging explorations of dominance and exploitation explored elsewhere in the production.

The nine collaborators who devised playing ‘the maids’ create a richly textured and multi-layered examination of global capitalism at a pivotal moment in history. They do so by realising a multi-perspectival vision that is of particular interest because it reflects the experiences of so called smaller nations, from which they each originate. It is exciting to find that Wales, as the host of this stimulating collaboration, is making a timely contribution to the global discourse on money and power.

It is also worth noting that playing ‘the maids’ examines gender inequality as poignantly as it does economic inequality. This quality is enhanced by the presence of five female actors in the cast, who bring their respective histories as women to the piece. As Jeungsook Yoo explains, there exists a ‘Korean obsession with ideal beauty’ that has fuelled a ‘boom of the plastic surgery and cosmetics industry’ in the country, which ‘resonated with the maids’ aspiration towards Madame’s beauty and wealth’. Both Korean actors satirise this yearning fascination with a highly-westernised concept of femininity in one short devastating scene that epitomises the tyranny of glamour.

Whereas, near the end of the play, Jing Hong Okorn-Kuo as Madame, immaculately dressed and poised, embodies the glamour of tyranny as she pronounces: ‘While in Hong Kong, or Singapore being served canapés and champagne by white-gloved waiters in white and gold uniforms, have you ever selected your next London apartment just for the view along the Thames?’ It is in moments like these, contrasting the vast wealth that is accumulating within narrow sections of the Asian economies with the new paradigm of austerity that is plaguing the West, that you can sense just how the tectonic plates of the world economy have discernibly (and possibly irrevocably) shifted.

Another source material for playing ‘the maids’ is Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-first Century. The book’s central thesis is that wealth is increasing becoming concentrated in the hands of tiny moneyed elites as the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of economic global trends in economic growth. The resulting unequal distribution of wealth causes social and economic instability, what Piketty calls the ‘endless inegailitarian cycle’.

Piketty’s phrase inspires the final image of playing ‘the maids’ that sees the entire cast running round in circles, holding aloft a puppet effigy of Madame, which represents their hopeless lack of agency in a world in which finance has become a self-feeding malignant force that devours the future. They spiral into complete darkness – the clatter of their shoes beating an insistent rhythm.

The image disturbs and saddens, as it should, but the creative ambition and intercultural reach of this extraordinary company provides sufficient inspiration to offer some consoling light.

playing ‘the maids’ is a collaboration between nine multi-disciplinary artists:

Director: Phillip Zarrilli

Dramaturg: Kaite O’Reilly

Cellist: Adrian Curtin

Sound: Mick O’Shea

Actors: Jing Hong Okorn-Kuo, Jeungsook Yoo, Sunhee Kim. Bernadette Cronin, Regina Crowley

(c) Phil Morris. Wales Arts Review.

Leave a comment

Posted in on performance, on writing

Tagged critism, cultural commentary, Gaitkrash, intercultural performance, Phil Morris, Phillip Zarrilli, Playing the Maids, Psychophysical performance, The Llanarth Group, Theatre P'Yut, Wales Arts Review